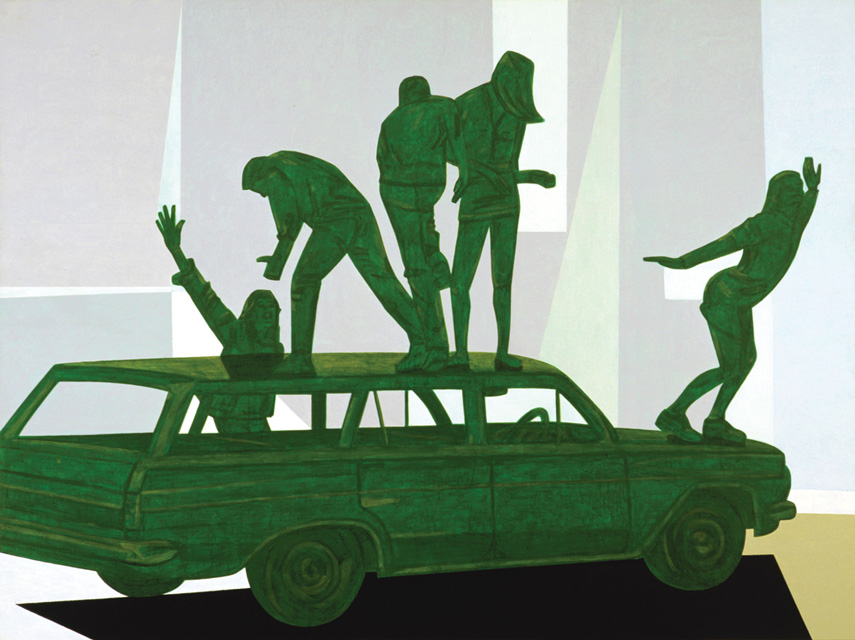

We wanna be free (1993) is a big painting, almost two metres high and two and a half metres wide. By making it so large, Campbell is emulating the western history paintings of the nineteenth-century. History paintings were grand figurative paintings representing public, political and historical subjects that were considered worthy of serious contemplation. Domestic and everyday subjects were painted on much smaller canvases, reflecting their private nature and lesser importance. We wanna be free is not a vignette. Because of its scale, Campbell shows youths living large in a large painting; for him, Australian suburban life and youth culture are important and worthy of our attention and contemplation.

Campbell's celebration of youth culture is not welcomed by all viewers. Some think that his chunky figurative style and familiar suburban subject matter constitute a 'dumbing down' of art, a revelling in failure to achieve or even strive for excellence. These critics are out of touch with some of the most important directions Australian contemporary art has taken, not just recently, but over the last twenty years. They also reflect the negative ideas about suburbia that, until the eighties and nineties, were dominant in Australian culture.

The representation of youth culture as equally deserving of attention as a history painting is at odds with the history of Australian art and criticism. It was only in the 1980s and 1990s that youth culture began to have a real presence in Australian art. As late as the 1990s, youth culture was derided as an aimless and valueless 'slacker' existence.

Previously, the Australian suburbs were represented by artists such as John Brack as a symbol of banality and blind consumerism. But artists like Campbell represent the suburbs as being full of life, excitement and meaning. It is not just Campbell's subject matter that challenges standards of art consumption: it is also the manner in which he portrays it. His use of thinly applied household enamel paint fails to meet traditional perceptions of quality and technique. His chunky, geometric, abstracted figures don't present youth as compliant or apologetic. Campbell's presentation of youth culture harks back to American teen films such as The Wild One (1954).

Campbell's art has been provided with a intellectual context by the influence of the British intellectuals, the Birmingham School, and the rise of cultural studies—a discipline that combines sociology and literary theory in the study of culture as a whole way of life—in Australian academia. This trend supports a perception of suburban life and youth culture as being worthy of serious critical contemplation by judging it on its own terms rather than measuring it against the values of a parent culture.

In Campbell's work, we can now read myriad cultural references, encounter a complex of values and sensibilities and see a portrait of a generation. The primary values of this generation are freedom and vitality, which he represents with their liberated gestures and the generally upward movement of the composition. One figure helps another climb onto the roof of the car as a girl dances on the bonnet; this is like a masthead for the mythology that 1970s youth culture represents freedom (as opposed to the more introspective and melancholy culture invoked by 'grunge’ music in the 1990s).

Jon Campbell has been a prime mover in the now well-trodden road of do-it-yourself culture and rock'n'roll values in contemporary art. He was one of the earliest artists to advocate that an artist might make their own fame by emulating rock'n'roll gestures in contemporary art. He has created work that in style and content was modelled on the simplicity of the three-chord song. He has created exhibitions such as Jon Campbell's Greatest Hits Vol. 1 (Glen Eira City Gallery, Melbourne, 1991), which incorporated rock'n'roll values and content into contemporary art.

We wanna be free is a key example of Campbell's work because it represents the triumph of youth culture—a crucial moment in Australian suburbia. In this sense it really is a history painting. As the young people dance on the roof and bonnet of the station wagon, it is easy to see how much Australia has changed since the days when John Brack’s family sat quietly and obediently in their car for a tour around the suburbs. Once a symbol of bourgeois aspirations, another box for consumers to pack their regimented lives into, the car is now the vehicle for a wild and liberated youth. The car has moved from a symbol of oppression and conservatism to one of liberation and carefree, leisurely radicalism.

- Lara Travis

Jon Campbell is represented in Australia by Darren Knight Gallery, Sydney.