Apocalypse is never far away in Jon Cattapan's paintings. His dense urban landscapes have something in common with Ridley Scott's movie Blade runner (1982) or Tim Burton's Gotham City in Batman (1989). They are either packed with an unhealthy and claustrophobic density, or they are sparse, awash in seas of toxic greens and blues. The mood is reminiscent of the apocalyptic literature of the English writer JG Ballard:

Many of the lagoons in the centre of the city were surrounded by an intact ring of buildings, and consequently little silt had entered them. Free of vegetation, apart from a few drifting clumps of Sargasso weed, the streets and shops had been preserved almost intact, like a reflection in a lake ... The bulk of the city had long since vanished, and only the steel supported buildings of the central commercial and financial areas had survived the encroaching flood waters.1

Cattapan's subjects to a certain extent have a literal source. He has spent time in the architecturally manicured environs of Canberra and the feverish, manic metropolis of Manhattan. He lives in St Kilda, an inner city seaside suburb of Melbourne, which has seen its share of the damned and the derelict. The city, for Cattapan, is a site of flux, ready to be washed away or consumed by flames.

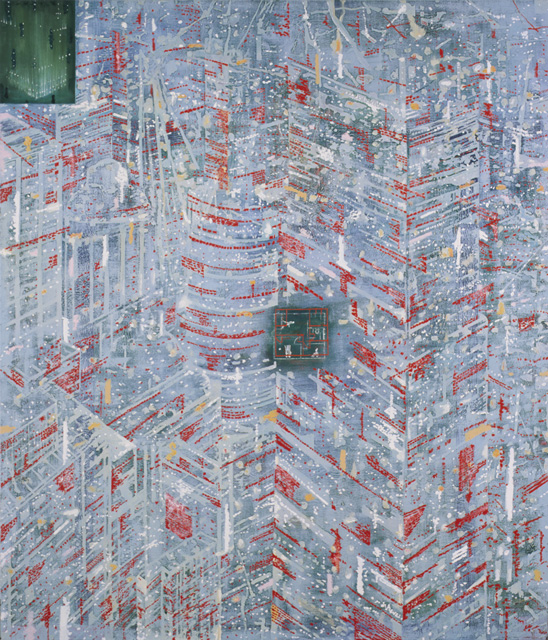

In The acid bath (1994), Cattapan's city becomes a dense matrix bound by cyberspace as much as mortar. The buildings are transparent, constructed with lines of dense information. The acid bath hails from a series Cattapan titled Pillars of salt, of which he has stated:

This cycle of works has developed out of my obsession with urban identity and the information overload in our contemporary world. In these paintings the lights and constant transmissions of a generic city are painted as disembodied 'bits' of data that drift around the picture plane. These floating apparitions that are like steaming, skeletal cityscapes (datascapes?) emphasise the transition of established orders. The paintings are about electronic information/memory, circuitry, architecture—systems of information.2

But in the age of cybernetic art, Cattapan almost perversely opts for the serious act of painting. Cattapan's Woden waiting (1992–93) is apocalyptic on a more physical level. The city of Canberra twinkles almost desperately in the background, awash in a sea of darkness. In the foreground is chaos, the aftermath of some bizarre accident where emergency teams labour.

Cattapan is a fan of Ballard, whose surreal fiction tackles similar themes as the artist such as the potentially murderous violence of the automobile. Writing in World Art magazine, Cattapan suggested that, 'Canberra, I think, is a "Ballard" kind of place. He might appreciate its absolute reality, its surreal emptiness, its national archiving institutions (where time stands still within), and above all the constant desire of its inhabitants to somehow temporarily disrupt the orderliness, to dissolve it, and in so doing, to take leave from their conscious selves.'3

In Cattapan's studio in late 2001, a large painting depicts a version of New York City. A gaping hole smoulders in the centre and a strange view of Gotham is accorded the viewer. The terrifying thing about this cityscape is that it was painted before the horrific events of September 11, as though, somehow, Jon Cattapan had dreamt that apocalyptic moment many months before it occurred. With the threat of global warming and rising sea levels, one wonders just what Cattapan is painting when his cities are awash.

Cattapan is not a social or environmental artist. He is also not a surrealist per se; nor, as a painter, is he a cyber artist. The inability to define Cattapan in terms of style and genre is arguably his greatest strength. In The acid bath and Woden waiting we have two extremes: one a metropolis of bits and bytes, a careering mass of electronic information: the other a murky portrayal of disaster awash in an unfriendly sea of dark blues. We know what happens when electricity meets water. Cattapan’s entire œuvre is awash with painterly threat. Like the best science fiction, these faraway scenarios are all too close to home.

- Ashley Crawford

Jon Cattapan is represented in Australia by STATION Gallery, Melbourne.